Ten years after her first feature film Palo Alto, Gia Coppola returns to the big screen this Wednesday to restore (hopefully) the image of the dynasty, especially after his grandfather’s “Megalopolesque” fiasco last year. For this, she armed herself with a formidable tactic… resurrect Pamela Anderson’s acting career, making her switch her famous red jersey for cabaret dancer heels and rhinestones.

It is in Las Vegas, the entertainment capital, that Shelly (Pamela Anderson) has been practising as a dancer in the Razzle Dazzle cabaret for 30 years. She has been the star of it during all these years and is obstinate on continuing. However, Shelly was pushed into retirement at age 50 when the institution closed. Between the ageism of the entertainment world and the reconnection with her daughter — until then neglected in favour of her work — she finds herself facing an unknown future.

We are immersed in a universe of stunning colours, between the shooting in 16mm film that allows you to feel the vibrance, and the rhinestones, furs and sequins dear to the entertainment world — especially the cabaret world — The Last Showgirl is a tribute to Las Vegas society and the American showgirls of the 80s. Unlike Paul Verhoeven’s Showgirls (1995), the film shows no performance. Indeed, the only choreography we are given to see is Shelly’s final audition at the end, a rather “narly” dance, which leaves us to say ‘All this for that ?’. We are so carried away in the passion of the dancer that her rather mediocre performance disappoints us.

The viewer is both lulled in a nostalgia for the “American star” created by visual mirages of de-focus assimilating the grains of the film to the brilliance of the glitter, but also in the disillusionment of the character of Pamela Anderson by close-ups on her face and her dark apartment. This is Shelly’s whole dilemma when the cabaret closes : stay and try to continue living her dream that is gradually dying, like her best friend Annette (Jamie Lee Curtis), a former dancer at the Razzle Dazzle, or leave Las Vegas and agree to retire.

Nevertheless, beyond the cloudy effect on the edges of the shot accentuating Shelly’s blurred future, the viewer finds himself especially troubled by the non-image and unsaid of the film. Should we be nostalgic for the 80s, the golden age of Vegas ? Pin-ups of the 1940s ? As Shelly tries to discern her future, we, spectators, try to discern her past, and the nostalgia that we try to impose on us.

Following the announcement of the termination of their show, Shelly feels her fame slip through her fingers, and returns to the harsh reality of show business, between poor salary and fear of being obsolete. Bit by bit, we realise Shelly’s denial. She lies about her age, does not realise the situation of the Razzle Dazzle, and has no notion of time — a feeling shared by Annette, who had not realised that it had been six years since she had left the cabaret.

Shelly reflects on the pursuit of her dream and sees her future — if she continues — in the current situation of Annette, also a former cabaret dancer, now hired as a waitress in a casino, where she will eventually ruin herself. It is therefore with great difficulty that she finds herself facing the ageism of the industry but also that of the objective she had, which can only be lived because we are ‘young and sexy’.

We learn, quite suddenly, in the middle of the movie, of the existence of her daughter, involving a new sacrifice : the neglect of the family in favour of work, first of her husband, then of her 22-year-old daughter, Hannah (Billie Lourd).

What cinema is for the Coppolas, the pursuit of the dream is for Shelly and Hannah. Although Hannah resents her mother for the neglect she has suffered all her life, she ends up telling her about her dream of being a photographer and travelling to Europe. Shelly recognises herself in her, having herself an artistic dream, going hand in hand with her passion for France and the world of Lido and cabaret.

At the Razzle Dazzle, a moving chosen family also formed between dancers Shelly, Marie-Anne (Brenda Song) and Jodie (Kiernan Shipka). They are the symbol of three generations, Shelly in her fifties, Marie-Anne in her thirties, and Jodie who is just 19 years old. While Jodie has just left home and begins to realise that she can no longer back down, Marie-Anne tries the castings and is already faced with negative comments about her age and body. The two girls then easily turn to Shelly, being, in their eyes, a legend, a mentor, but above all, a mother.

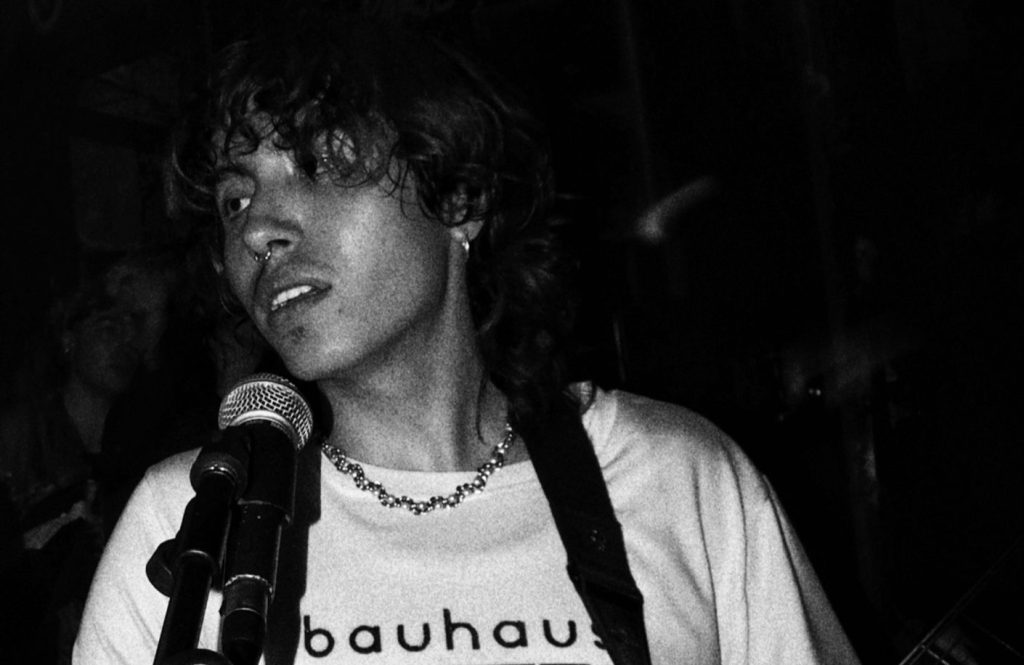

The “mise en abîme” of Pamela Anderson’s life is interesting but it seems that Gia Coppola was afraid that the sad conclusion of the dancer would manifest into the life of the actress. This would explain (spoiler alert!) The happy ending in extremis, which invokes a magical reconciliation with her daughter and colleagues. It goes without saying that there seems to be a certain trend in the cinematographic world. As with Demi Moore in The Substance (2024), the idea of directors Coralie Fargeat and Gia Coppola to renew the career of icons of the 90s to give the middle finger to patriarchal criteria seems to be the right vein. Actresses give themselves 1000% to their role, as a matter of life or death (career). In the end, the former playmate plays almost her own role in the last minutes of the film, creating extreme empathy for the viewer, transforming the 16mm film into 16mm of eyelight precipitation.

The Last Showgirl is a powerful film about the last vestige of a changing city of entertainment. Gia Coppola shows us the ambivalences between professional and personal life through Shelly’s maternal figure, and between the pursuit of the dream and the fatal reality of society. The power of Pamela Anderson’s play allows us to recognise the (often forgotten) artistic beauty of cabaret. It is an ode to art and its existence in a decadent Las Vegas, to the grace of the forgotten and people who have clung to a dream all their lives, which have allowed them to be seen and to feel alive.

Laisser un commentaire