A sound system that tears out your eardrums, rhythms with tathycardic beats, and naked bodies under dim lights, the rave has begun…. In Berlin, there are many techno clubs : Tresor, Renate, Watergate, or — of course — the famous Berghain. A true religion that today earns the city its nickname of “capital of techno”. Yet the genre was born on the other side of the Atlantic, in Detroit. So, how did the Berlin techno scene rise to the title of “capital” ?

Jesus is not white, neither is techno. In the 1980s, Detroit was a city in crisis. The automotive industry settles and thrives there — at the expense of the population. Highways are built, imposing brutal urban segregation : on the left, the white and rich neighbourhoods ; on the right, the black ghettos. Step by step, the white population fled to the residential suburbs, abandoning the city centre to people of colour — downtown where robots have more rights than humans. In this post-apocalyptic setting, a new music emerges : This is Techno.

African-American DJs seize it and see it as a social, political and economic escape. A sound for us by us, designed for black DJs and clubbers. Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson – now nicknamed « the Holy Trinity » – lay the foundations of a radically new genre : mechanical, futuristic, but above all anchored in a social reality. A way to dance on the ruins, to fantasise about other possible worlds, in a present saturated with dead ends.

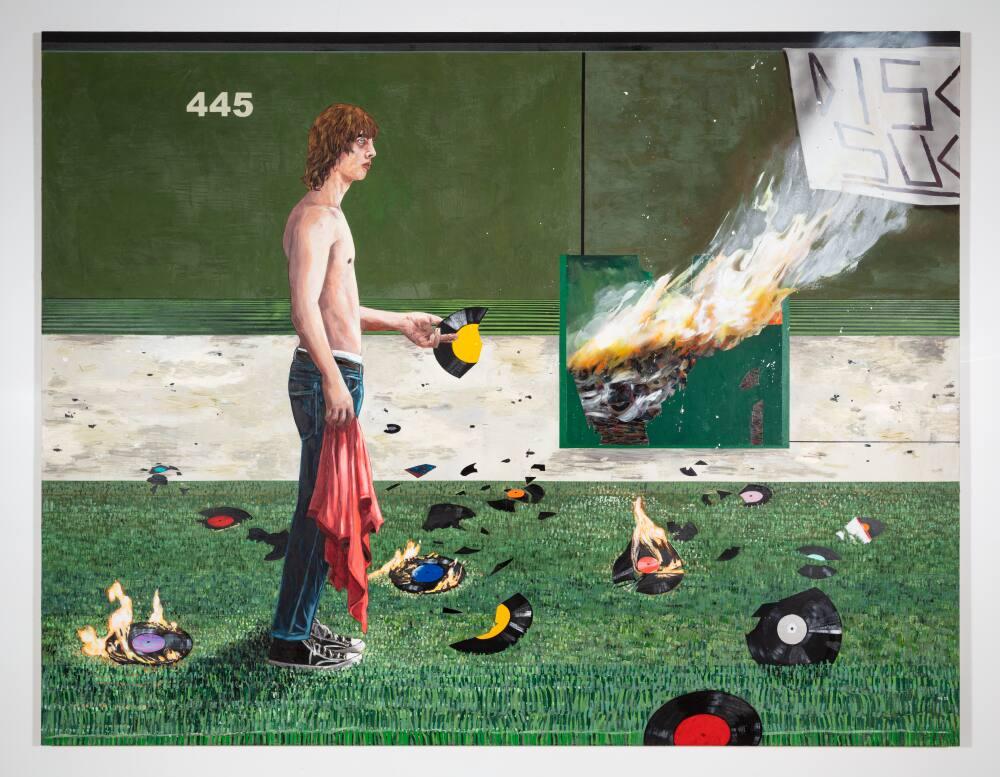

But techno doesn’t come out of nowhere. It inherits from disco, which already in the 70s, had opened its dancefloor to marginalised communities — queer, black, latinx — in an explosion of freedom. Disco was already a space of communion, which saw in particular the black community celebrate its identity, its culture and its history. Disco music carried in it the sound revolution that would follow with techno : futuristic aesthetics, drum machines, synthesisers… All this transits from New York, to the machines of Detroit pioneers. Disco died publicly in 1979, lynched by the conservative white rockers of the Disco Sucks movement. But its offspring is there, and it’s making noise.

This sound crossed the Atlantic in the late 1980s. Berlin was then a grazed city, fractured by forty years of Cold War. While in Detroit, the division was drawn by the highway, in Berlin, it took the form of a Wall — a border that was both physical and mental. On the one hand, West Berlin, lulled by an American liberalism, hedonistic and disillusioned. On the other, East Berlin, locked behind the concrete curtain, where the government monitors dreams as well as conversations. In 1989, the Soviet bloc faltered, the protests intensified, the Wall trembled, then fell on November 9th. And it is precisely in this moment of tension that techno found a fertile ground in the capital.

The city is under construction and its brownfields are becoming improvised clubs. In 1991, the Berlin artist Dimitri Hegemann redeveloped an empty space to make it his club : Tresor. Located in the centre of the cement scar that was the Wall, the Treasury imposes itself as a nerve centre of reunification, and propels techno to the heart of the city. Very quickly, the Berlin youth adopted this music as the soundtrack of its revolution — it is a ravolution. What was a minority becomes a global phenomenon. The spark launched by Detroit, in Berlin turns into a fire.

Today, techno resonates in clubs around the world, from Ibiza’s electric line-ups to the intimate lives of Boiler Room, through tunnels and disused spaces – as an echo of the first Berlin raves.

But behind this tone of a raw freedom emerges the mutation of the genre, it is gentrified. What was a cry of the margin has become, over time, a cultural product, a bankable aesthetic. Underground has sold itself at the price of hype, warehouses have given way to private clubs, and sounds, once transgressive and anarchist, are now fuelling the capitalism of cultural tourism.

Techno has gone from the African-American ghetto of the 1980s to the Berlin squats of the 1990s, to end up today in the white and overpriced scenographies of the Sónar – emptied of its political and racial anchorage. The genre, by globalising, has become white. More than a question of skin colour, the bleaching of the genre is the progressive erasure of the struggles that saw it born (in Detroit) and popularise (in Berlin) – in favour of smooth and disengaged consumption. From underground to mainstream, this robotic sound seems to progress on a sanitised road, dispossessed of what was left of human.

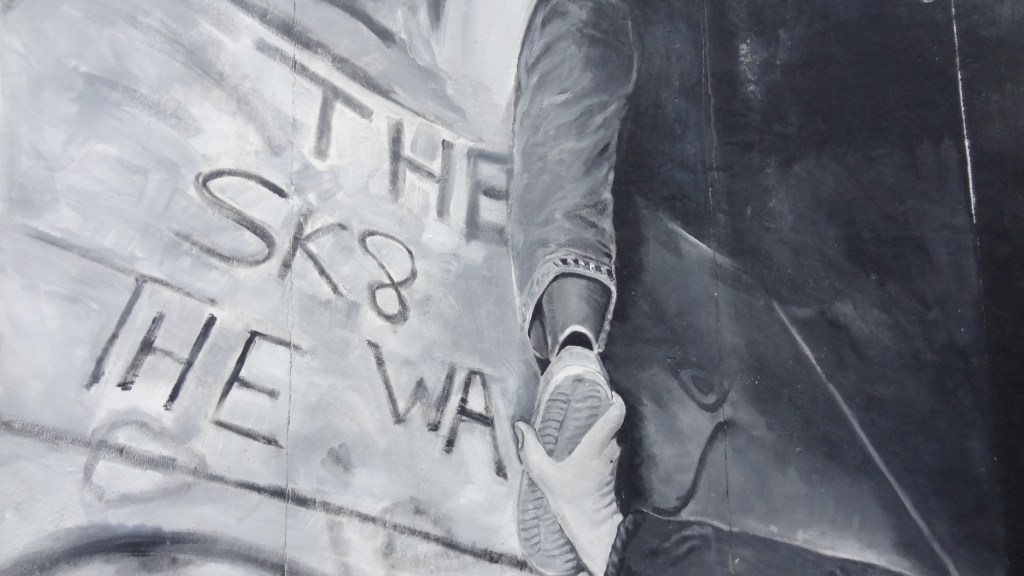

Fortunately, pockets of resistance remain. In protest processions, some faithful divert the altar of the club to preach in the street. With militant beats and stroboscopic trucks, collectives make the crowd sing and dance. This is the case of MC danse pour le climat, a Parisian group that diverts the codes of rave to put them at the service of the climate cause. Their presence in the public reactivates the sacred profane of the rave : a community, festive, and above all, insurgent rite. Thus, the original Masses of Detroit and Berlin are replayed, not to entertain, but to awaken. A ravolution, in the liturgical sense of the term, through trance and protest.

Thus, Berlin’s status as the world capital of techno descends from a church of resistance that, over time, has been manipulated and then sanitised. The whitewashing of techno is not an accidental drift, it is the result of a well-established mechanic. Like jazz yesterday, or like rap today, which has exchanged struggles against lifestyle, this seems to be the fate of black music that enters the mainstream. Techno has not lost its faith, it changed gods.

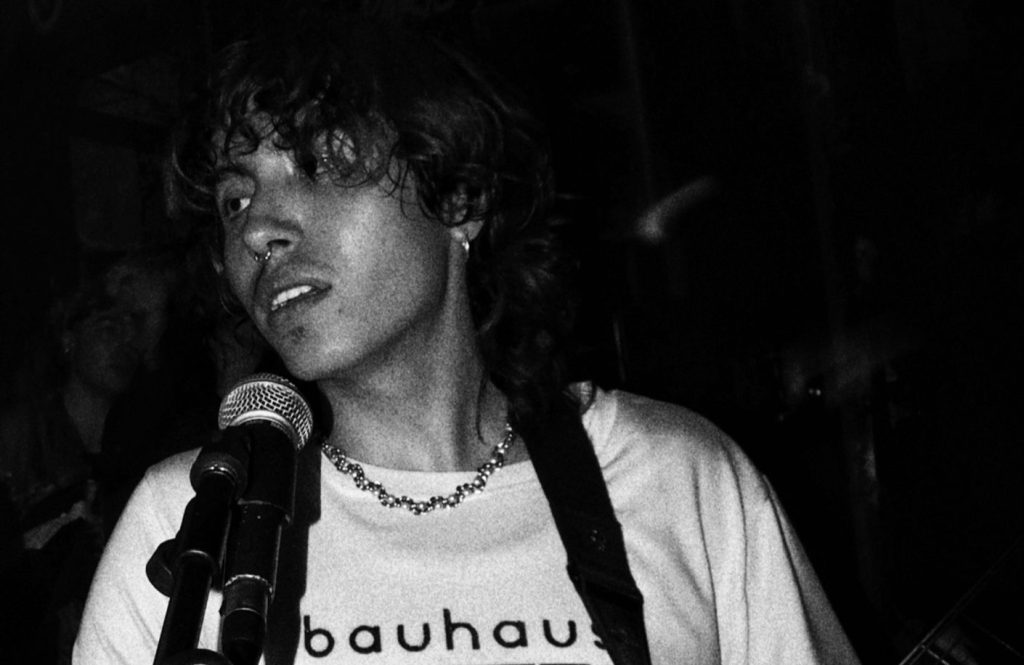

Conversation with Ima

Ima is a Parisian DJ from Côte d’Ivoire. Before making the turntables vibrate, it is in the fashion world that she evolves. She first studied cosmetic, and at the same time as her sewing classes, she was on shootings as a makeup artist and hairdresser. After ten years in the fashion world and a permanent contract that has become suffocating, confinement acts like a click. Ima reconnects with music, and begins to mix, crossing genres. Coupé-décalé, bouyon, rap, rnb, techno… Ima doesn’t give herself any limits.

Today, after eclectic sets in Geneva for Traxi, in Barcelona for Voodoo Club, or in Paris for Rinse, she becomes viral on social media with her concept of « ivoire techno ». Ima tells us about this musical guilty pleasure and the direction she wants to give to this sound !

HOW DID YOU FALL INTO TECHNO?

When I started mixing, around 2021/2022, I don’t know why, but I directly tried to combine techno with rap, afro, bouyon… In fact, all possible and unimaginable genres. I was trying to mix everything. But I also had to adapt to the mainstream, so I set familiar lyrics – from French and American rap – on these beats.

I don’t really know where this passion comes from. I didn’t have a group of friends to go out with on a techno or electro party. I listened to it alone at home. But there was something calling me there. When I started mixing, I was making funk-techno mixes, which I quickly deleted. It’s something I’ve always done in my corner, in secret, and that I didn’t assume — and that I still assume moderately.

On the other hand, I immediately recognised myself in the sets of black techno artists like DJ Minx or Carl Craig. I have the impression that Detroit’s techno is not the same as the one we hear in Europe today. It is softer, less dark. I like everything – hard and soft – as long as it’s well worked.

ON TIKTOK, YOU MIX TECHNO WITH AFRO-CARIBBEAN BEATS. IN PARTICULAR, YOU MADE A MIX WITH COUPÉ DÉCALÉ THAT YOU CALLED : « IVOIRE TECHNO ». HOW DID YOU COME UP WITH THIS IDEA ? WHAT IS THE INTENTION BEHIND IT ?

For everything that is Caribbean, I have the impression that bouyon is already techno – in terms of bpm, rhythm, and the way it takes me. Same for Afrobeat, there are many biama and coupé-décalé rhythms at 160 bpm, with very hard instruments, very close to electronic music.

When I wanted to listen to Afro-techno, I struggled to find some. On Youtube, I typed « afro-tech » and I’ve only found afro-house… I had to look to niche artists on Soundcloud, like Bonaventure. So I said to myself: « I might as well do it myself ».

For Tiktok, I saw that everyone was talking about it – even my mother, even my family. I said to myself: « Stop being a boomer », and I started. And then, techno and coupé-décalé are two sounds that people love separately. I knew that by mixing them, it could make people talk.

What I discovered while making these videos is that there are many black people, westaf, young girls who look like me, who listen to this. But we tell ourselves that it’s not for us. While in fact, if you go back to the beginning, techno was created by black people. When were these barriers put in place ?

I myself was ashamed to listen to techno. Shamed to say that I was doing it. I was saying : « I do that, I like it, but… » to soften things up.

FOR YOU, PLAYING THIS SOUND IS A POLITICAL GESTURE OR IS IT JUST BECAUSE YOU LIKE IT ?

Both. Even if I didn’t realise at first, doing techno will be political. Playing music from where I’m from is a message. And then it’s also a way to make people love coupé-décalé who, at the start, were not necessarily attracted to it. The opposite also works : there are people who listen to afrobeat rather than techno, and who discover a sound they like with « ivoire techno ».

Uniting genres also unites people.

I played for the first time in a party recently – but what I was most proud of was that it was an event in support of the homeless. I have always tried to be in contact with people who are against injustice.

Before, I listened to techno in my corner… but today, I find it on the street, in protests. Music is our way to escape from everything that is happening in the world – but if we can escape while staying engaged and conveying a message, then we do it.

WHEN WE GO BACK TO THE ORIGINS OF TECHNO IN DETROIT, THERE WERE BLACK FIGURES, BUT VERY FEW WOMEN HIGHLIGHTED. DO YOU FEEL THAT THERE IS A LEGACY TO TAKE UP, OR EVEN TO REBUILD TODAY ?

Totally. There is a lot to do about the place of women in the world of DJing, night, and techno in particular. We are just as legitimate as others to play this music. We need to be more highlighted, considered, validated… to arrive and be directly put on a pedestal.

It’s always this work of « twice as much » when you’re a black woman. But I remain positive. I really think we are already walking this path. I wouldn’t even have been able to play electronic music if I hadn’t had examples of black female DJs like Ohjeelo, Crystallmess or Bonaventure. There may have been few, but now there are, and there will be even more.

This is just the beginning.

Laisser un commentaire